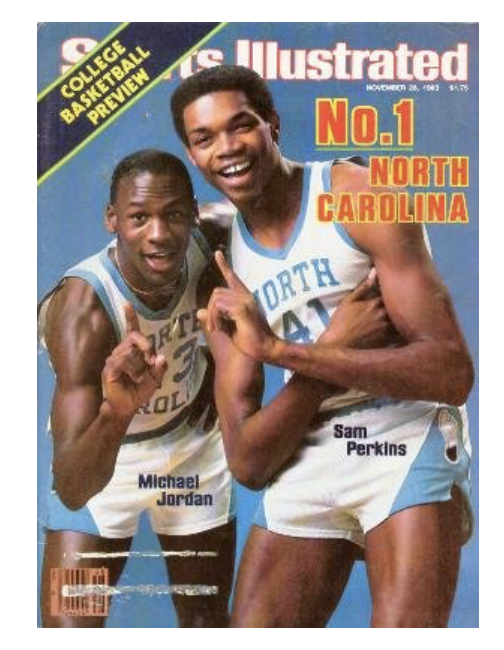

He was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., won an NCAA title at North Carolina in 1982, was ACC Freshman of the Year, was a two-time first-team consensus All-American, named USA Basketball’s Male Athlete of the Year, had his UNC jersey retired, made the NBA All-Rookie first team, won an Olympic gold medal and was a Top 5 pick in the 1984 NBA Draft, arguably the best of all time.

Yes, all of that is part of Michael Jordan’s legacy. All of that also is part of Sam Perkins’ legacy.

While Perkins’ NBA career wasn’t as decorated as Jordan’s, he certainly established himself as one of college basketball’s most prolific players, and also was an NBA force to be reckoned with. A power forward and center, Perkins was the No. 4 overall pick by the Dallas Mavericks in 1984 – picked one selection behind Jordan and one selection before Charles Barkley — and played 17 seasons.

The 6-9, 235-pounder played so well at UNC from 1980-’84 that not only did the Tar Heels retire his jersey, but he also was inducted into the College Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018.

“It’s a good gratification and appreciation for what you did there,” Perkins told Mavs.com. “I didn’t ask for it, and when you don’t expect something and it comes all of a sudden from around the corner and in your lap, it’s almost like, ‘Wow, I did something that made a difference.’

“But when the call came from the Hall of Fame, I thought somebody was playing a joke.”

It was no joke. Perkins was the Most Valuable Player of the 1981 ACC tournament as a freshman, a consensus second-team All-American as a sophomore, and a consensus first-team All-American as a junior and senior.

He also was in the New Orleans Superdome – along with a whopping 61,612 fans – when Jordan buried a game-winning jumper with 17 seconds left to give the Tar Heels a 63-62 victory over Georgetown in the 1982 NCAA championship game. And Perkins corrected what had been widely reported – saying that UNC coach Dean Smith drew up the final play for James Worthy, not for Jordan.

“He drew up a play for Worthy, and we swung it to the strong side to get it to Worthy to see if he could do something because he had the hot hand,” Perkins said. “But they left Michael all alone. He was wide open on the other side.

“I guess it took everybody by surprise that a freshman would take the shot. But it was a good read by Jimmy Black (who passed the ball to a wide-open Jordan).”

Still, Perkins knew there was plenty of time left on the clock for Georgetown to pull out an improbable victory. And everything fortunately went the Tar Heels’ way.

“We had to play defense on the last shot, and for some reason Worthy was out of position and I remember guarding two people,” Perkins said. “But who would I guard if that ball went up – Patrick Ewing or (Ed) Spriggs? I’m glad they didn’t even get a shot off because I was underneath there all by myself. So, I’m glad Fred Brown threw it to Worthy for the win.”

As he and millions of others are busy watching the popular ESPN docuseries The Last Dance – the final two episodes are Sunday starting at 8 p.m. — Perkins remembers the days when he played with Jordan at UNC.

“It was fun,” he said. “We had a team that was just balanced. We weren’t really cocky, but we just knew we had a great team, but we had to prove ourselves every night. Michael came in as a freshman (in 1981) and gave us a big lift.

“Usually freshmen don’t really contribute as much as they have in the past, but Michael contributed and he gave us a big boost. We had a lot of guys on that team that were playmakers and smart, so we found success in coach Smith by doing what we do and by playing together.”

As a freshman, Michael Jordan, according to Perkins, wasn’t the Michael Jordan everyone later became accustomed to seeing flying all over the court and dominating games.

“But he was still the same guy as far as personality-wise,” Perkins said. “His presence, as you can see on this documentary, was more valued than anything, because guys straightened up a little bit. They saw how hard he works, so everybody wanted to do just as well as he did.”

Perkins said Jordan never belittled his teammates in practice at UNC, as is shown on numerous occasions in The Last Dance. Meanwhile, after playing with the Mavs from 1984-90, Perkins played with Magic Johnson and the Los Angeles Lakers from 1990-93, then with Gary ‘The Glove” Payton and the Seattle SuperSonics until 1998, and with Reggie Miller and the Indiana Pacers from 1998-2001.

During his six-year tenure with the Mavs, Perkins saw the folks in North Texas wrap their arms around the team. In that span, the Mavs produced a 281-211 record and won at least 50 games on two occasions.

During his six-year tenure with the Mavs, Perkins saw the folks in North Texas wrap their arms around the team. In that span, the Mavs produced a 281-211 record and won at least 50 games on two occasions.

The franchise’s only other prosperous tenure occurred during the Dirk Nowitzki era when the Mavs manufactured 11 consecutive 50-win seasons starting in 2001, capped by winning the 2011 NBA title.

“They had one signature guy, which was Mark Aguirre, and then they came in with Rolando (Blackman), and as time went on they just got the pieces,” Perkins said. “They had Jay Vincent, Derek Harper, and they gradually built to a point where they were going to make some noise in the Western Conference.

“When I finally got there and Roy (Tarpley ) came (in ’86), we had a chance to compete for the title and at least go to the Western Conference Finals.”

Of course, being with the Lakers meant Perkins was a teammate of Johnson, and was there on Nov. 7, 1991, when Johnson announced that he was retiring from the NBA because he had tested positive for HIV.

“We were practicing at Loyola Marymount, and we came in, and Magic wasn’t there, and (Lakers coach Mike) Dunleavy told us to stop playing, stop whatever you’re doing and go home and get back to the arena by 1:30,” Perkins said. “Well it was already 11 o’clock, so pretty much we had to just go home, get dressed and come back, but we didn’t know why we were there or anything like that.

“So once we got there (Dunleavy) broke us the news that Magic had HIV, and we just couldn’t believe it, because HIV and AIDS was pretty prevalent, just as this coronavirus is now. So when (Johnson) came in, he announced it, we were there to be supportive for his announcement and it just changed the outlook of our team. Our leader was gone, we had the worst time on the court because we couldn’t do anything after that, and it just affected us off the court as well, because it was a detrimental blow to us and to the community. The fans were all about Magic Johnson, LA was Magic Johnson, and Magic Johnson was LA., so we were just devastated.”

Later, when Johnson was considering returning to the NBA, players didn’t warm up to the idea.

“A lot of guys didn’t want to play against him because we didn’t know how (HIV) was obtained, we didn’t know how you could get it – through sweat glands, through kissing, through saliva, through somebody getting scratched,” Perkins asked. “We didn’t know what was going on, so we had to educate ourselves.

“I went to Johns Hopkins to take in the full story and educate myself so I wouldn’t be afraid. It was panic throughout the whole league because it was just one of those things where we thought Magic was on his death bed like any minute. I don’t think they had a vaccine or any medicine at the time – they didn’t know what to do – and we thought Magic was probably on his way out. But miraculously and thankfully he’s still here.”

In the meantime, after helping the Mavs take the Lakers to a Game 7 of the 1988 Western Conference Finals, Perkins helped the Lakers reach the 1993 NBA Finals. He also helped Seattle reach the 1996 NBA Finals.

On both of those trips to the Finals, Perkins’ team lost to Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. And after helping Indiana advance to the 2000 NBA Finals, Perkins and the Pacers fell victims to Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O’Neal and the Lakers.

Affectionately known by his nicknames – Big Smooth and The Big Easy – Perkins was a huge fixture in the Seattle community during his days with the Sonics.

“I had gotten traded from the Lakers and my thing was trying to be (prominent) within the community and giving back and things of that nature,” Perkins said. “Seattle was more of a community that you can do all of that because it was diverse there, and it was much smaller than LA.”

Thus, in addition to playing for the Sonics, Perkins put on concerts in the community, and also had his own radio show.

“I had a radio show on Sunday night,” he said. “That was my passion at the time, and I wanted to get into communications, and I even had what they call now a podcast.

“My passion turned out to be music and giving back and Special Olympics and doing all those things while playing up there (in Seattle). It was gratifying just to know that you can help people and do whatever you can because they loved the Sonics and were trying to be another team that competes for championships.”

One musician who Perkins brought to Seattle for a concert was Dallas’ own Erykah Badu, who hadn’t even released her first album yet.

“Seattle had a music genre of different groups and is known for rock and roll, but you couldn’t really get familiar with any R&B singers because of the lack of black stations there,” Perkins said. “So when Erykah Badu came, when we booked her we couldn’t believe it. And once she came, part of Pearl Jam came, Sam Smith came, George Howard came, and we had a lineup of different people from Jay-Z’s label at the time. We had a good time doing all of that.

“The Sonics were supportive, and then we had Nancy Wilson (of Heart) come for a Christmas type of concert. I can’t believe I was doing all of this while I was playing, because it took a lot of work to get sponsors and going to different meetings to getting the OK from the city – the permits and all those things — just to have the concert.”

Currently the treasurer for the National Basketball Players Association, Perkins also runs a youth summer camp in Chapel Hill, N.C., which focuses on the development of basic basketball skills, but unfortunately has been canceled for the upcoming summer due to the coronavirus.

“It’s been going on for 21 years,” Perkins said. “That camp is run my myself and family members and Carolina people and different coaches in the Carolina area. But I don’t want to put kids or my staff or directors in danger.”

A solid stretch-four before the term was in vogue, Perkins tied an NBA record on Jan. 15, 1997, when he came off the bench and converted eight 3-point field goals without a miss while scoring 26 points in 23 minutes during Seattle’s 122-78 win over Toronto.

Meanwhile, Perkins was so valuable to the Mavs that Rick Sund – the team’s director of player personnel at the time – believes his jersey should be hanging in the American Airlines Center rafters.

“One of the most underrated players for the Mavericks was Sam Perkins,” Sund said. “He had the ability to cover small forwards, centers, power forwards. His knowledge and feel for the game were perfect chemistry matchups with Aguirre.”

Perkins laughed at Sund’s jersey comment, adding that since he wore the same No. 41 jersey as Nowitzki, that his number has actually already been retired.

“Rick is probably being nice and saying things that are gratifying, but I don’t think I’m even close to having my jersey retired because I left (the Mavs after six seasons),” Perkins said. “If I had stayed, maybe, but for those six years that I was there, I played my position.

“I just wish that I was more aggressive with that team because that’s the kind of team that you build on and learn from. But I learned a great deal just from interacting with teammates and people, which helped me to improve with each team that I went to. With the Lakers it was a little different, but here in Dallas I wish I was a little more aggressive and maybe had some more fortitude to my game.”

Perkins did have enough fortitude to become one of the greatest college basketball players of all-time. He also carved out a pretty productive 17-year NBA career.

Twitter: @DwainPrice

Share and comment